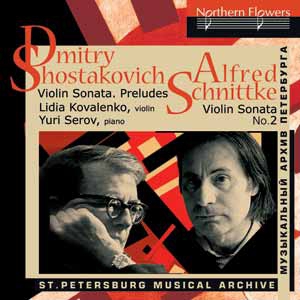

CDs

NF/PMA 9902

Recorded at the St.Catherine Lutheran Church (St.Petersburg), April 18 & May 2, 2000

Sound recording & supervision: Victor Dinov

Editing: Victor Dinov

Text: Yuri Serov. English translation: Sergey Suslov

Design: Oleg Fakhrutdinov & Anastasia Evmenova

|

Dmitry Shostakovich (1906–1975) |

||

|

Sonata for violin and piano, Op. 134 (1968) |

||

|

1. |

Andante |

10.01 |

|

2. |

Allegretto |

6.28 |

|

3. |

Largo–Andante–Largo |

15.39 |

|

Four Preludes |

||

|

4. |

Prelude in C major |

1.16 |

|

5. |

Prelude in H major |

0.48 |

|

6. |

Prelude in C-sharp minor |

1.45 |

|

7. |

Prelude in D minor |

1.22 |

|

Alfred Schnittke (1934 - 1998) |

||

|

8. |

Sonata No.2 for violin and piano. Quasi una Sonata (1968) |

7.24 |

|

|

|

|

|

“In honour of the 60th anniversary of David Fedorovich Oistrakh”, reads the friendly dedication made by Dmitry Shostakovich to the Sonata for Violin and Piano. The background of this masterpiece, this acme in the composer’s chamber works (moreover, in the 20th century’s music on the whole) was later commented by the great violinist in his memoirs as follows: “Dmitry Dmitriyevich got an idea to give me a birthday present, that is, to write for me a new Second concerto, completing it right by my 60th anniversary. But he miscalculated the finishing date by one year. The Concerto was ready by my 59th anniversary. It seems Dmitry Dmitriyevich believed that the error had to be corrected. That was how the sonata for violin and piano appeared… I could not expect that, although I had been dreaming for years of a violin sonata written for me by Shostakovich”.

The piece was completed in the autumn of 1968. The composer was already seriously ill by the time. Despite the world-wide recognition, renown, and unrestricted possibilities for performance of new works, the variety of images created by Shostakovich in his last period of life is surprisingly sad. Elements of perception of the tragic in the human existence are matched in his compositions with serene melancholy, sometimes with light irony. The active spirit is minimized, pondering and insight becoming the main points. And it was chamber music, as the will and confession of the great composer, became his key genre of composition in his last years.

The Sonata is a cycle not quite usual in its structure. Its beginning and end, that are calm and restrained, frame a rapid and vigorous Allegretto. The First Movement begins in a theme passing through all the twelve tones of the scale, an open reminder of Arnold Schoenberg’s dodecaphonic system which had been in existence for several decades by that time. A soft, unhurried Andante leaves an impression of some omitted utterance. Mysterious sounds are transformed in the reprise into nearly mystic ones, anticipating and preparing the main act. The appearance of a dance-like second theme just emphasises the brittle and illusory nature of the core material. The Second Movement is a non-stop motion, a ‘devilish’ scherzo toccata so typical for Shostakovich music. The drive of rhythm and energy, the harsh and coarse themes, it all seems to be taken from a previous active and filled life. Rushing rapidly in, the music suddenly stops; the opening fanfares lead to the variations of the Finale. Proceeding through a chain of reincarnations of every kind, exposing the main theme from every side, the development reaches its apex, the dramatic climax of the entire sonata: after the virtuoso cadences of the piano and violin, the master tune of the variations comes back again, but this time powerfully driven. In a moment, the form of the entire composition becomes clear, as if lit with a bright flash. The climax leading of the main theme crowns the grand edifice like the dome of a magnificent cathedral. On the last pages, in the coda, the mysterious episodes from the first movement come back, leaving the impression that the great master could say more but never did…

24 Preludes for Piano were written by the composer in the years 1932 and 1933, — as he himself used to put it, ‘in a train’ between Leningrad and Moscow. Shostakovich had just finished his opera Lady Macbeth, and frequently had to visit the capital for business related to its production. Addressing miniature pieces after the monumental and tragic opera might seem somewhat unexpected - at the first glance. In any case, the string of preludes, emotionally, differs from the severe atmosphere of Lady Macbeth so greatly that it is hard to believe that these two opuses are so close to each other in time, and even that they belong to the same author at all. Irony, humour, satire - and limitless emotion and tenderness. These are the two main poles around which these marvellous miniatures are built. A generous gift of melody, and brilliant use of the instrument’s capabilities by the young composer, remind of the best achievements of the Russian school of pianism.

Fourteen of the twenty–four preludes were transcribed for violin and piano by Dmitry Tsyganov, an outstanding violinist, a friend of Shostakovich, and his partner in ensembles. These arrangements, which carefully retain the instructions by the author, be it on the texture and tone, or even minor remarks on dynamics and articulation, soon became a popular and integral element of the Soviet violin repertoire, successfully rivalling the original piano version.

The Second Violin Sonata by Alfred Schnittke begins with an abrupt piano chord, like a rifle shot. It blows up the silence — and the very notion of the style, established in many centuries. It is the start of the Polystylistics era in the works of Schnittke, and moreover, for the Soviet music in general. The subtitle given by the composer to his work is "quasi una Sonata", echoing Beethoven’s eternal “Moonlight Sonata”, Sonata quasi una Fantasia. Beethoven in his masterpiece steps out into the domain of the Romantic music, being unable to stay within a classical sonata’s framework. Schnittke, on the contrary, is annoyed with the sonata form as such. The contradictions and contrasts are too strong, and just the startling freedom of utterance should lay a foundation for setting up something new.

The world of harmony and disharmony, unbearable noise of sounds and silence in its pre–existent definition, episodes of hard rhythm and anarchy of tempos — such are the basic “construction materials” of this astonishing, unexampled sonata. But there is another important aspect, that of relations between Person and Society, the lone voice of man and the powerful roar of crowd; of confusion, perplexity, fear, and submission of an individual before the eternal and irresolvable problems of mankind. Allusions of music of the past — Beethoven, Brahms, Liszt, and the monogram motif

The Second Sonata by Alfred Schnittke, despite considerable difficulties faced by both performers and listeners, became one of the most repertoire-attractive violin sonatas of the twentieth century. Without uttering a word, the composer in fact tells a great many things in this work, so exceedingly complex in its musical embodiment and language. The established ideals fall into pieces under the troubles of today’s world, the quietude of days of old can never be regained; different, and sometimes painful, efforts are needed to create a new harmony and a new equilibrium.

|